The ELSI Infrastructure for Scalable Electronic Structure Theory

The O(N3) Kohn-Sham Eigenproblem

Kohn-Sham density-functional theory (KS-DFT) [1]

- Workhorse for molecular and materials simulations

- Large number of software implementations

- Running on world’s leading HPC resources

Computational bottleneck of KS-DFT

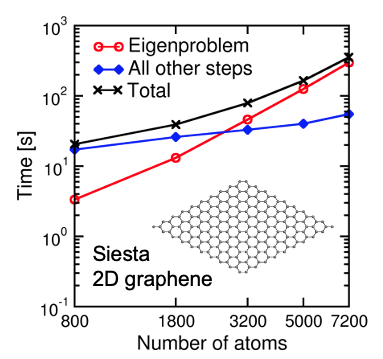

With local and semi-local exchange-correlation functionals, the solution of the eigenproblem \(H C = S C \Lambda\) becomes the computational bottleneck in large-scale calculations.

- O(N3) complexity of a dense eigensolver

- O(N) in almost all other operations (generally true with localized basis functions)

Test case:

- 2D graphene supercell models

- KS-DFT calculations with the SIESTA [2,3] code

- 13 basis functions per atom

- PBE semi-local exchange-correlation functional

Fig. 1: Timing of KS-DFT calculations of a series of graphene supercell models with the SIESTA code. Calculations were performed on the Edison supercomputer with 80 nodes (1,920 CPU cores).

Fig. 1: Timing of KS-DFT calculations of a series of graphene supercell models with the SIESTA code. Calculations were performed on the Edison supercomputer with 80 nodes (1,920 CPU cores).

ELSI: The ELectronic Structure Infrastructure Project

Overview

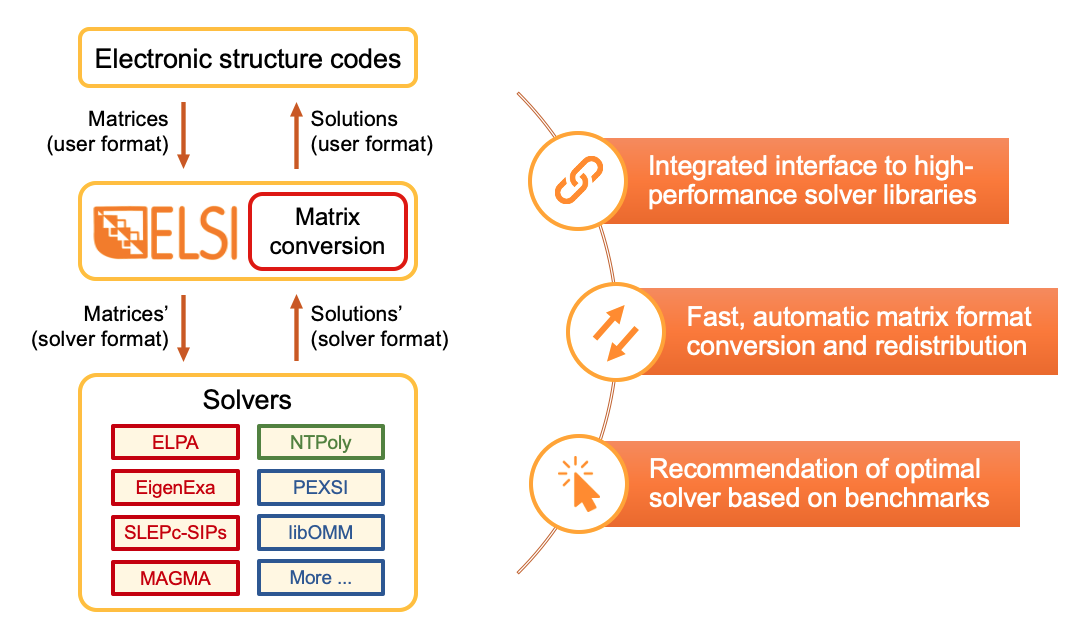

ELSI [4,5] provides an integrated software interface to connect electronic structure codes with high-performance eigensolvers and density matrix solvers. The unified ELSI API handles the conversion between different units, conventions, matrix formats, and programming languages.

Fig. 2: ELSI serves as a bridge between electronic structure codes and solver libraries.

Fig. 2: ELSI serves as a bridge between electronic structure codes and solver libraries.

Feature highlights

- Eigensolvers and density matrix solvers via a common API

- Matrix formats: Dense or sparse local storage, 1D/2D block-cyclic distribution or any arbitrary distribution, parallel interconversion between different formats

- Parallel solution for spin-polarized and/or periodic systems

- GPU acceleration eigensolvers

- Reverse communication interface (RCI) for iterative eigensolvers

- Programming interfaces: Fortran, C, C++

- CMake build system supports Cray, GCC, IBM, Intel, PGI compilers

- “MolSSI best practices”: Documentation, wiki, issue tracker, automated tests, …

- From laptops to supercomputers (Cobra, Cori, Summit, Theta, …)

- Adopted by:

- Part of the CECAM Electronic Structure Library project (ESL): Distribution of shared open-source libraries in the electronic structure community [10]

Find the source code on the Download page or check out the git repository here.

Solvers supported

- Distributed-memory eigensolvers

- ELPA: Dense eigensolvers based on one-stage and two-stage tridiagonalization [11-13].

- EigenExa: Dense eigensolvers based on one-stage tridiagonalization and penta-diagonalization [14].

- SLEPc: Sparse, iterative eigensolver based on shift-and-invert spectral transformation and spectrum slicing [15,16].

- Distributed-memory density matrix solvers

- Shared-memory eigensolvers

- Distributed-memory BSE eigensolvers

- BSEPACK: Special-purpose dense eigensolvers for solving the Bethe-Salpeter equation [23].

Application Programming Interface (API)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

call elsi_init

call elsi_set_parameters

do while (geometry not converged)

do while (SCF not converged)

call elsi\_{ev|dm}

end do

call elsi_reinit

end do

call elsi_finalize

- Designed for rapid integration into a variety of electronic structure codes

- Compatible with common workflows

- Self-consistent field (SCF): line #4

- Multiple SCF cycles (geometry relaxation or molecular dynamics): line #3

- Supports density matrix solvers and eigensolvers on an equal footing: line #5

- All technical settings adjustable for experienced users: line #2

Solver Performance Benchmark

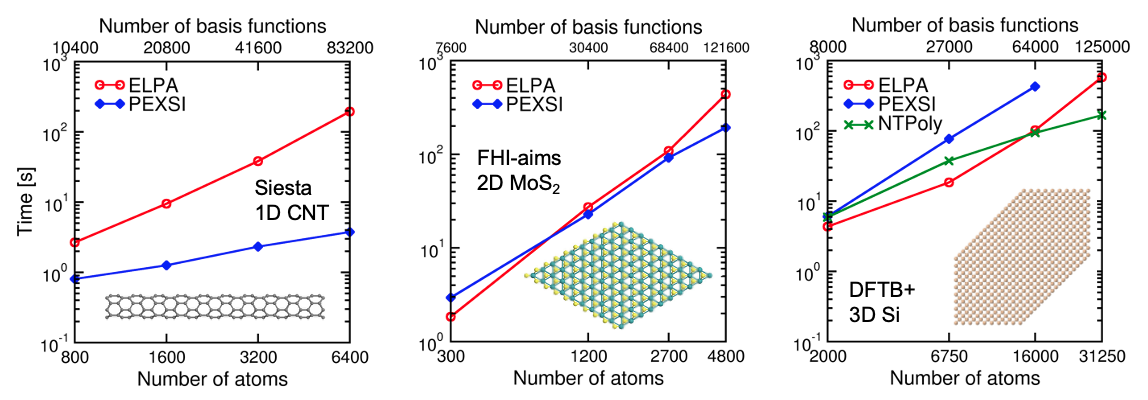

We have performed a systematic set of solver performance benchmarks [4,5], based on which we identified the expertise regime of each solver. An automatic solver selection is proposed and implemented in ELSI.

- ELPA: O(N3) but small prefactor. Efficient for small to medium systems.

- PEXSI: O(N) and O(N1.5) for 1D and 2D systems, respectively. Efficient for large, low-dimensional systems.

- NTPoly: O(N) for sufficiently sparse matrices. Efficient for large systems with an energy gap.

Fig. 3: Performance of ELPA, PEXSI, and NTPoly in (a) KS-DFT calculations of quasi-1D carbon nanotube models with the SIESTA code, (b) KS-DFT calculations of 2D MoS2 monolayer models with the FHI-aims code, and (c) DFTB calculations of 3D silicon supercell models with the DFTB+ code. Calculations were performed on the Cori supercomputer (Haswell partition) with 80 nodes (2,560 CPU cores).

Fig. 3: Performance of ELPA, PEXSI, and NTPoly in (a) KS-DFT calculations of quasi-1D carbon nanotube models with the SIESTA code, (b) KS-DFT calculations of 2D MoS2 monolayer models with the FHI-aims code, and (c) DFTB calculations of 3D silicon supercell models with the DFTB+ code. Calculations were performed on the Cori supercomputer (Haswell partition) with 80 nodes (2,560 CPU cores).

GPU Accelerated Eigensolvers

Shared-memory solver: MAGMA

The MAGMA project [22] aims to develop a dense linear algebra framework for heterogeneous architectures consisting of manycore and GPU systems. The GPU-accelerated, tridiagonalization-based eigensolvers in MAGMA have been added to the ELSI interface since v2.4.0.

On a single shared-memory compute node, MAGMA delivers a significant speedup over the CPU LAPACK. However, large eigenproblems can easily exceed the memory capacity of a single node, thus they must be solved on distributed-memory parallel computers.

| GaAs supercell | Natom | Nkpt | Nbasis | Ncore | LAPACK time [s] | MAGMA time [s] | speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 x 3 | 54 | 36 | 1,836 | 18 | 25.0 | 10.1 | 2.5 x |

| 4 x 4 | 128 | 14 | 4,352 | 14 | 150.6 | 12.0 | 12.6 x |

Distributed-memory solver: ELPA

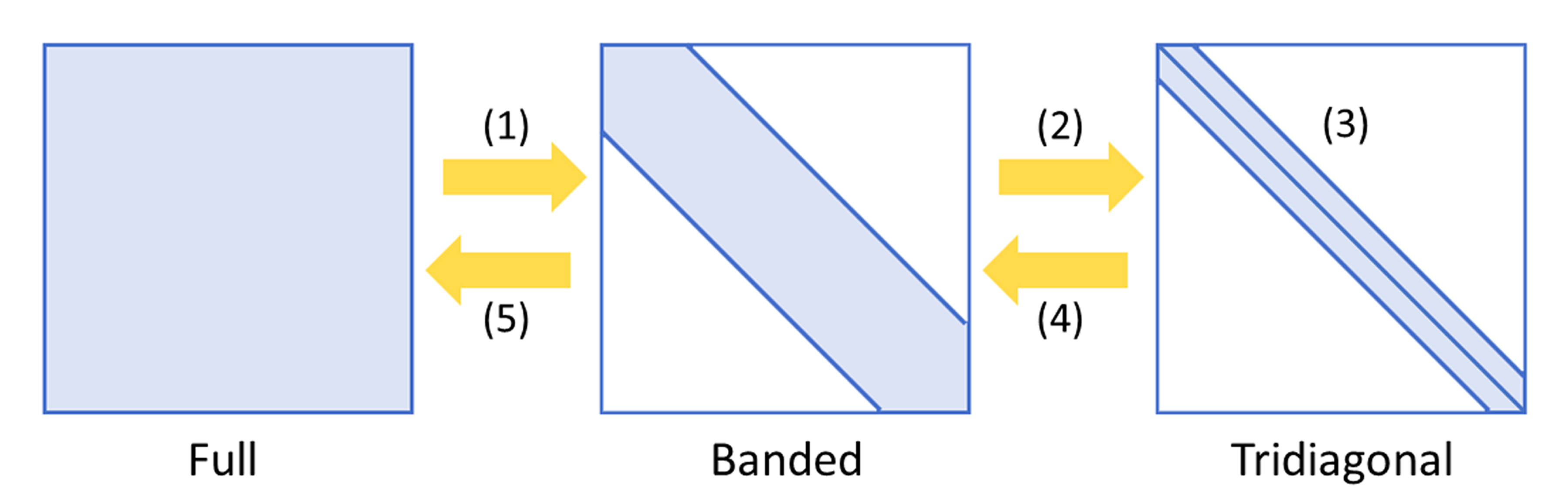

The two-stage tridiagonalization algorithm

The ELPA2 eigensolver features an efficient two-stage tridiagonalization method consisting of five computational steps:

- Full matrix to banded matrix.

- Banded matrix to tridiagonal matrix

- Solution of tridiagonal eigensystem

- Tridiagonal eigenvectors to banded eigenvectors

- Banded eigenvectors to full eigenvectors

Fig. 4: Five computational steps of the two-stage tridiagonalization algorithm used by ELPA2.

Fig. 4: Five computational steps of the two-stage tridiagonalization algorithm used by ELPA2.

The two-stage method has been shown to enable faster computation and better parallel scalability than the conventional one-stage tridiagonalization [11,12]. The matrix-vector operations (BLAS level-2) in the one-stage tridiagonalization can be mostly replaced by more efficient matrix-matrix operations (BLAS level-3) in the two-stage algorithm.

Development and optimization

The initial proof-of-concept GPU porting of the ELPA2 eigensolver was programmed by Peter Messmer, NVIDIA. This version is mostly based on the cuBLAS library to accelerate dense linear algebra operations.

The robustness and efficiency of the GPU ELPA2 code, and its scalability of GPU ELPA2 on distributed-memory (multi-nodes) hybrid CPU-GPU architectures, have been enhanced by our recent development and optimization [13]:

- Added a CUDA kernel for Householder transformations in the computation of eigenvectors

- Eliminated a restriction on the block size of the distributed matrices

- Optimized GPU memory usage and CPU-GPU communication

- Added GPU support of generalized eigenproblems

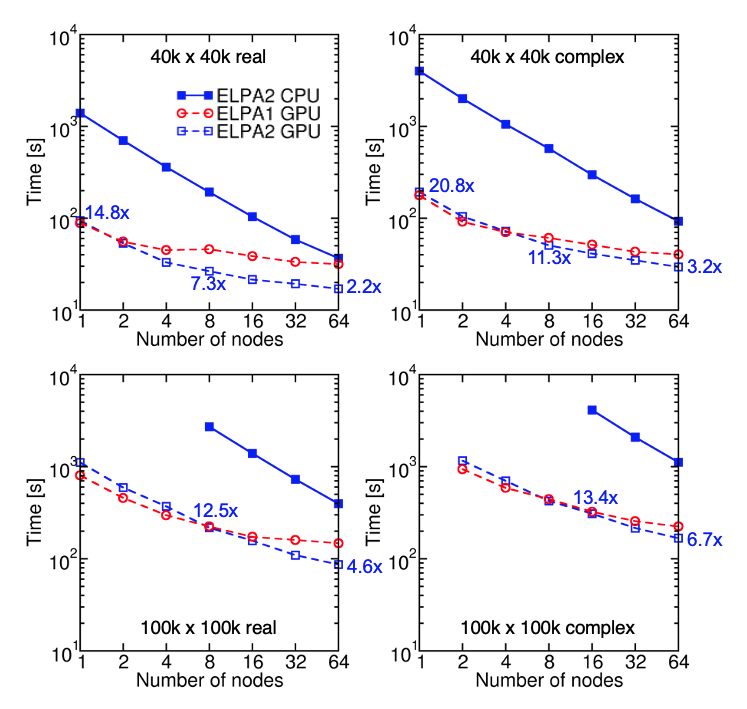

Performance

The performance of the optimized GPU ELPA2 solver was benchmarked on the Summit supercomputer. Depending on the size of the eigenproblem, the GPU speedup can exceed 20x.

Fig. 5: Timings of CPU-ELPA2, GPU-ELPA1, and GPU-ELPA2 for randomly generated, real symmetric and complex Hermitian matrices of size $N$ = 40,000 and 100,000. All eigenvalues and eigenvectors are computed. The gray dotted lines indicate ideal strong scaling. Tests are performed on the Summit supercomputer. Each node of Summit has two IBM POWER9 CPUs and six NVIDIA Volta GPUs.

Fig. 5: Timings of CPU-ELPA2, GPU-ELPA1, and GPU-ELPA2 for randomly generated, real symmetric and complex Hermitian matrices of size $N$ = 40,000 and 100,000. All eigenvalues and eigenvectors are computed. The gray dotted lines indicate ideal strong scaling. Tests are performed on the Summit supercomputer. Each node of Summit has two IBM POWER9 CPUs and six NVIDIA Volta GPUs.

Application in electronic structure calculations

We demonstrate the efficiency of GPU-ELPA2 in actual materials simulations. KS-DFT calculations of a supercell model of Cu2BaSnS4 (1,536 atoms, 41,088 basis functions) were performed with the FHI-aims code on the Summit supercomputer. Time spent on the solution of the generalized eigenproblem in one SCF step is shown below, comparing the CPU and GPU versions of ELPA2.

| Nnode | CPU time [s] | GPU time [s] | speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1438.0 | 85.0 | 16.9 x |

| 2 | 746.1 | 56.1 | 13.3 x |

| 4 | 400.2 | 39.3 | 10.2 x |

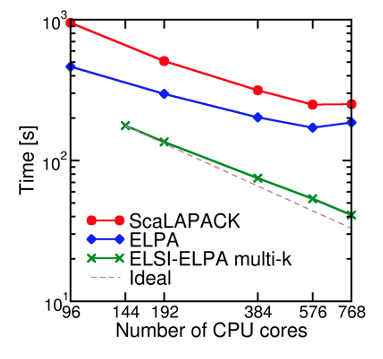

Connection to Electronic Structure Code Projects

The ELSI interface has been fully integrated into the DFTB+, FHI-aims, DGDFT, and SIESTA code projects, providing users of these codes with access to all the solvers supported in ELSI. The benefit of using the ELSI interface and the solvers it supports has been shown in the benchmark section. We here demonstrate the usage of the ELSI interface in periodic calculations. The SIESTA-ELSI interface can exploit the full parallelization over k-points and spin channels [3]. This means that these calculations can use two extra levels of parallelization compared to the previous diagonalization schemes in SIESTA (standard ScaLAPACK and ELPA eigensolvers), substantially enhancing the parallel efficiency of the code.

Fig. 6: Performance improvement from the use of the extra level of parallelization over k-points in SIESTA using the ELSI interface. Benchmark system is bulk Si with H impurities (1,040 atoms, 13,328 basis functions, 8 k-points).

Fig. 6: Performance improvement from the use of the extra level of parallelization over k-points in SIESTA using the ELSI interface. Benchmark system is bulk Si with H impurities (1,040 atoms, 13,328 basis functions, 8 k-points).

Outlook

We are and will be working on

- The integration of ELSI into more electronic structure code projects

- GPU acceleration in more components of ELSI

- support of more high-performance solvers targeting the next-generation supercomputing architectures

The ELSI project is intended to be an open forum, fostering international, interdisciplinary collaborations that benefit the entire electronic structure theory community. Learn more through the following communication channels:

References

- Kohn and Sham, Physical Review 140 (1965), A1133-1138. link

- Soler et al., Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 14 (2002), 2745-2779. link

- García et al., The Journal of Chemical Physics 152 (2020), 204108. link

- Yu et al., Computer Physics Communications 222 (2018), 267-285. link

- Yu et al., arXiv: 1912.13403 (2019). link

- Aradi et al., The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 111 (2017), 5678. link

- Hourahine et al., The Journal of Chemical Physics 152 (2020), 124101. link

- Hu et al., The Journal of Chemical Physics 143 (2015), 124110. link

- Blum et al., Computer Physics Communications 180 (2009), 2175-2196. link

- Oliveira et al., arXiv: 2005.05756 (2020). link

- Auckenthaler et al., Parallel Computing 37 (2011), 783-794. link

- Marek et al., Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 26 (2014), 213201. link

- Yu et al., arXiv: 2002.10991 (2020). link

- Imamura et al., Progress in Nuclear Science and Technology 2 (2011), 643-650. link

- Hernandez et al., ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 31 (2005), 351-362. link

- Keceli et al., Journal of Computational Chemistry 37 (2016), 448-459. link

- Lin et al., Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 25 (2013), 295501. link

- Jia and Lin, The Journal of Chemical Physics 147 (2017), 144107. link

- Corsetti, Computer Physics Communications 185 (2014), 873-883. link

- Dawson and Nakajima, Computer Physics Communications 225 (2018), 154-165. link

- Anderson et al., LAPACK users’ guide (1999). link

- Tomov et al., Parallel Computing 36 (2010), 232-240. link

- Shao et al., Linear Algebra and its Applications 488 (2016), 148-167. link

Acknowledgments

- We thank the developers and contributors of the ELSI project.

- ELSI is a Software Infrastructure for Sustained Innovation - Scientific Software Integration (SI2-SSI) software infrastructure project supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under award 1450280. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

- Victor Yu was supported by a fellowship from The Molecular Sciences Software Institute under NSF grant OAC-1547580.

- This research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725.

- This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.