Randomized Methods for Quantum Chemistry

Introduction

- Strong correlation among the electrons in many molecules and materials gives rise to unique and useful properties (e.g. catalytic behavior, superconductivity).

- Calculating properties of strongly correlated systems is expensive, requiring the solution of linear algebra problems involving large matrices. Many conventional approximations fail for strongly correlated problems.

- We are developing randomized methods able to efficiently solve linear algebra problems in quantum chemistry involving large matrices by stochastically introducing sparsity and then averaging.

- Our ongoing work is focused on reducing statistical error and increasing the sizes of chemical systems to which our methods can be applied.

All methods described here are discussed in more detail in our forthcoming paper.

Stochastic sparsification

We use a 2-step process1 to randomly compress a vector to a user-specified number of nonzero elements. First, we identify a set of elements that will be preserved exactly on the basis of their relative magnitudes. Then, we randomly select a subset of the remaining elements using a correlated sampling procedure. Elements are selected with probabilities proportional to their magnitude. All other elements are zeroed.

\[\begin{pmatrix} 0.90 \\ -0.025 \\ 0.025 \\ 0.025 \\ -0.025 \end{pmatrix} \to \begin{pmatrix} \color{red}{0.90} \\ -\color{blue}{0.05} \\ 0 \\ \color{blue}{0.05} \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\]Figure 1: A schematic showing the stochastic compression of a vector to 3 nonzero elements. Elements designated to be preserved exactly are shown in red, while those selected during the sampling procedure are shown in blue.

Introducing zeros in this way allows for the storage of vectors in sparse format, with significantly reduced memory requirements.

Estimating the ground-state energy

We estimate the ground-state energy (least eigenvalue) of the full configuration interaction Hamiltonian matrix, \( \mathbf{H} \), using an iterative procedure. In each iteration, the current vector is multiplied by the matrix \( \left( \mathbf{1} - \varepsilon \mathbf{H} \right) \), where \(\varepsilon\) is a small, positive parameter. The resulting vector is then stochastically compressed. Although \( \mathbf{H} \) is sparse, the number of nonzero elements in each of its columns renders this step expensive for many chemical systems of interest. We address this by factoring \( \left( \mathbf{1} - \varepsilon \mathbf{H} \right) \) and compressing the vector obtained after multiplication by each of its factors.3, 4

After each iteration, the energy is estimated from the resulting vector \(\mathbf{v}^{(\tau)} \) as

\[E^{(\tau)} = \frac{\mathbf{v}_\text{ref}^* \mathbf{H} \mathbf{v}^{(\tau)}}{\mathbf{v}_\text{ref}^* \mathbf{v}^{(\tau)}}\]where \(\mathbf{v}^{(\tau)} \) is an approximation to the ground-state eigenvector, obtained from an approximate method. An estimate of the ground-state energy, as well as its associated standard error, are obtained by averaging over all iterations. We also report the statistical efficiency, which is inversely proportional to the square of the standard error.

Extensions for error reduction

Initiator approximation

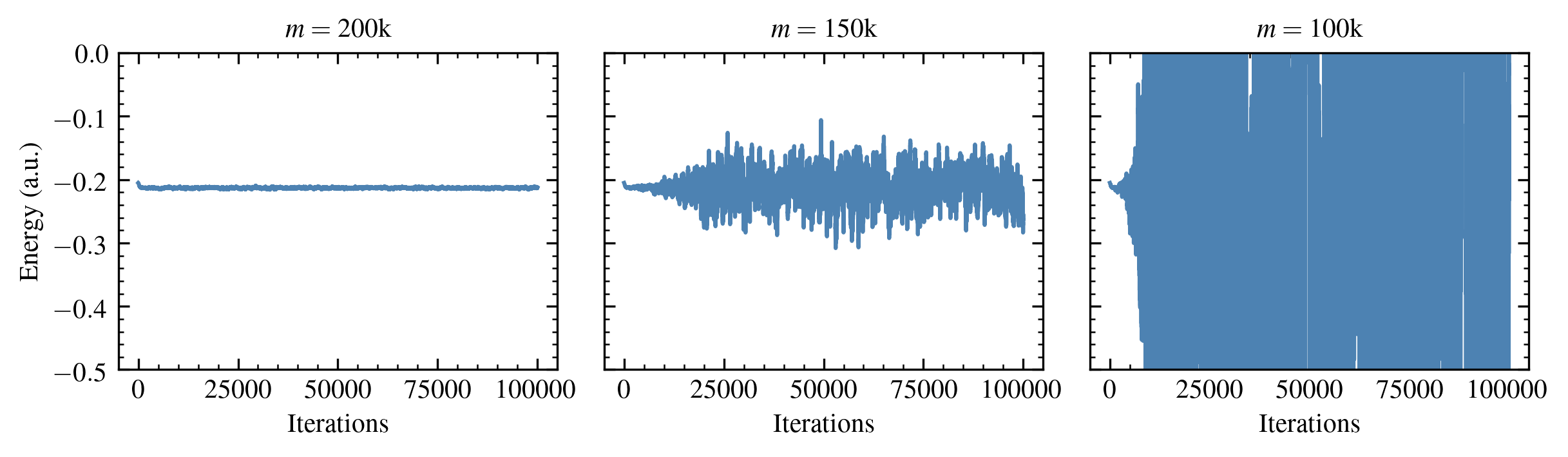

The following figure shows the behavior of the energy estimates \(E^{(\tau)}\) for a small chemical system as a function of the user-specified number of nonzero elements retained in compression operations \( m \).

Figure 2: Energy estimates for the Neon atom in the aug-cc-pVDZ basis.

Figure 2: Energy estimates for the Neon atom in the aug-cc-pVDZ basis.

The standard error in the average energy increases substantially as \( m \) is decreased below a system-dependent threshold. Since the cost of these calculations (per iteration) scales with \( m \), this renders it difficult to apply this method to larger chemical systems, for which greater values of \( m \) are required.

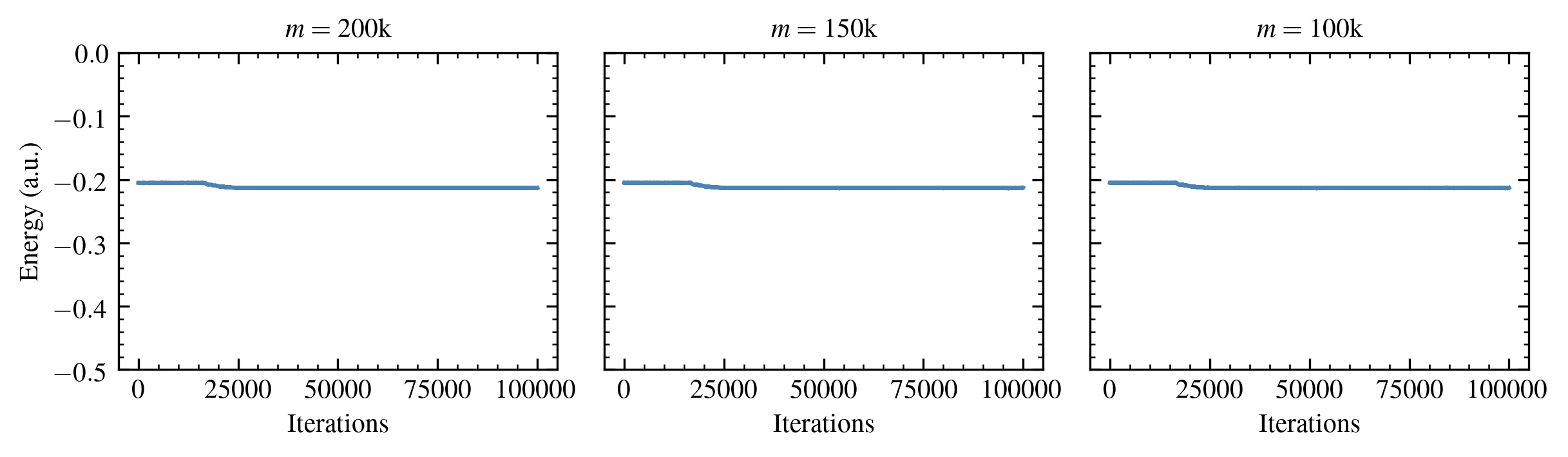

We address this using the initiator approximation,5 in which only the elements in the current iteration with a magnitude greater than an “initiator threshold” \( n_a \) are allowed to introduce weight in the next iteration on vector elements that were previously zero. This greatly reduces the standard error (increases the statistical efficiency).

Figure 3: Energy estimates for the Neon atom in the aug-cc-pVDZ basis obtained using the initiator approximation.

Figure 3: Energy estimates for the Neon atom in the aug-cc-pVDZ basis obtained using the initiator approximation.

This technique is an “approximation” because it increases a bias that increases with increasing \( n_a \). Nonetheless, the associated reduction in statistical error makes this worthwhile for many chemical systems of interest.

Alternative Hamiltonian matrix factorization

We developed an alternative approach to factoring the matrix \( \left( \mathbf{1} - \varepsilon \mathbf{H} \right) \) designed to further reduce the statistical error. Some of the matrix factors have fewer nonzero elements, making the associated matrix-vector multiplication operations cheaper, and their elements are cheaper to compute on the fly. We see that this alternative factorization yields consistent improvements in statistical efficiency while reducing overall execution times by as much as 17% for the three chemical systems tested.

Implementation considerations

Since receiving the MolSSI fellowship, I have developed a C++ library that supports several different stochastic compression algorithms. Some subroutines are applicable to any matrix or vector, while others have features related specifically to the FCI problem. My library supports MPI parallelism, so vectors are stored in sparse format distributed among multiple MPI processes. Matrix-vector multiplication is parallelized, as is stochastic compression. I developed a protocol for performing stochastic compression that minimizes communication among processes.

Ongoing work

- Extending these methods for the estimation of excited-state energies

- Applying these methods to the Hubbard-Holstein model, a minimal model of superconductivity

- Extending the applicability of these methods to larger systems through improvements in code and stochastic sampling methodology

Acknowledgements

Samuel M. Greene was supported by a fellowship from The Molecular Sciences Software Institute under NSF grant OAC-1547580. Additional funding for this project was provided by the NSF through award DMS-1646339 and the Advanced Scientific Computing Research Program within the DOE Office of Science through award DE-SC0020427. The Flatiron Institute is a division of the Simons Foundation.

References

- L.-H. Lim and J. Weare. SIAM Rev. 2017, 59, 547-587.

- G. H. Booth, A. J. W. Thom, and A. Alavi. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 054106.

- S. M. Greene, R. J. Webber, J. Weare, and T. C. Berkelbach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 4834-4850.

- V. A. Neufeld and A. J. W. Thom. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 127-140.

- D. Cleland, G. H. Booth, and A. Alavi. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 041103.