ATESA: an Automated Aimless Shooting Workflow

Introduction

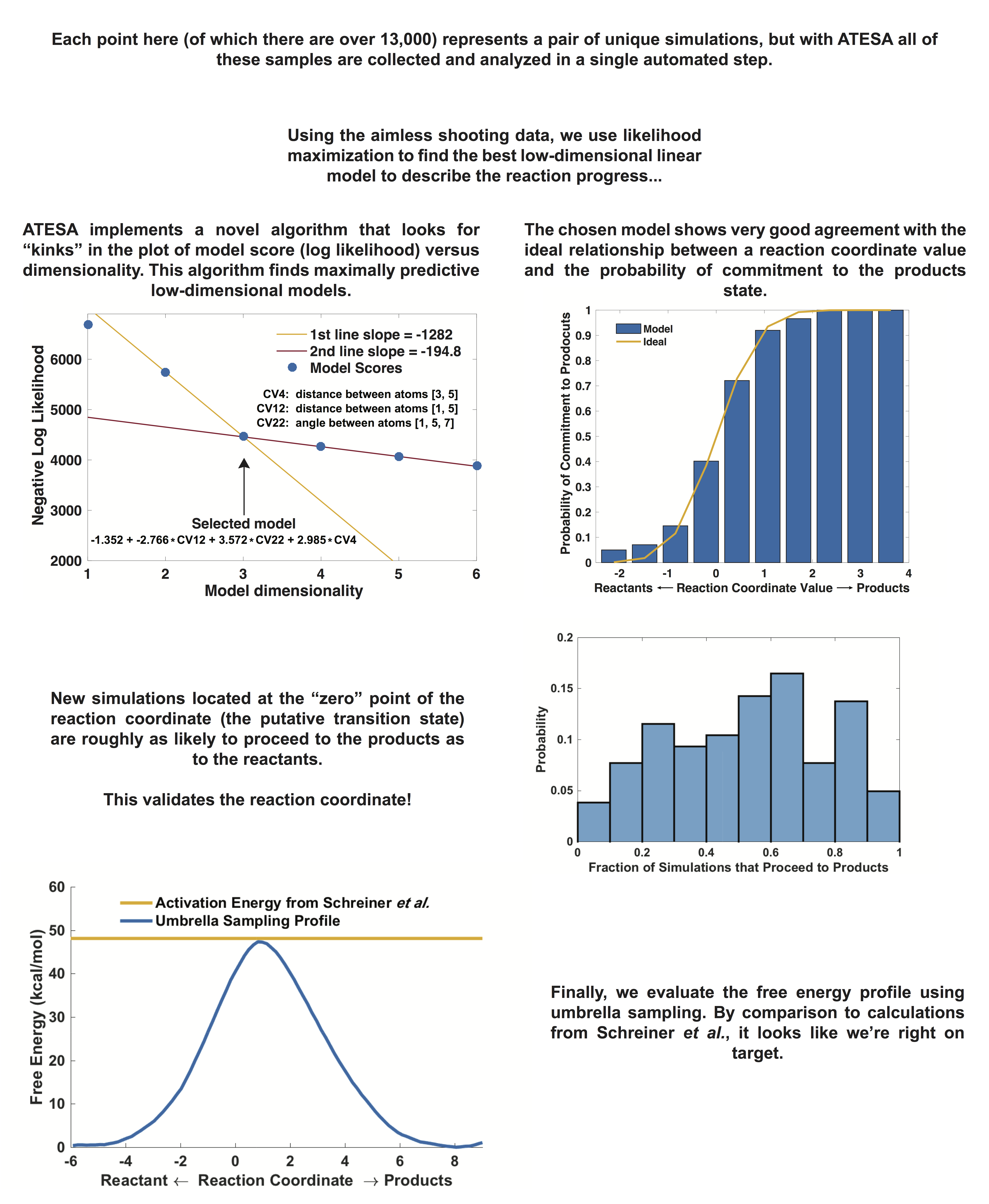

Transition path sampling methods are an indispensable tool for computational study of the dynamics of rare events in molecular simulations. However, access to advanced sampling techniques like transition path sampling is generally restricted to experts with the knowledge and resources to carefully set up, curate, and analyze the potentially huge number of simulations that constitute a complete study. ATESA (“Aimless Transition Ensemble Sampling and Analysis”) is a new open-source software program written in Python that automates a full transition path sampling workflow based on the aimless shooting algorithm, with a particular focus on extending accessibility to non-expert users who are familiar with the basics of molecular simulations, but not necessarily with programming or advanced sampling methods. It also implements novel methodological contributions that should be of use to anyone performing aimless shooting. Here, we will introduce ATESA and showcase some of the results of its automated transition path sampling process flow for an example reaction — including finding an initial transition state, sampling with aimless shooting, building a reaction coordinate with inertial likelihood maximization, verifying that coordinate with committor analysis, and measuring the reaction energy profile with umbrella sampling — all without leaving the software.

ATESA was built on the MolSSI computational chemistry cookiecutter using open-source best practices wherever possible. More complete documentation than is available here can be found on the project’s documentation webpage.

Rare Event Sampling and ATESA

What is a rare event?

Molecular simulations are a powerful tool for investigating the workings of chemical systems at the extremely small scale. However, due to technical limitations, simulations are necessarily quite limited in scope and cannot replicate the time- and length-scales relevant in laboratory studies. This can be particularly troublesome when the important feature of a system is a chemical reaction or transformation with a significant activation barrier; although such an event may take place very quickly in the eyes of an experimentalist, it could take years of computer time before the same event might be expected to occur just once in a simulation. This is what is meant when we call certain reactions or transformations “rare events”.

What is aimless shooting?

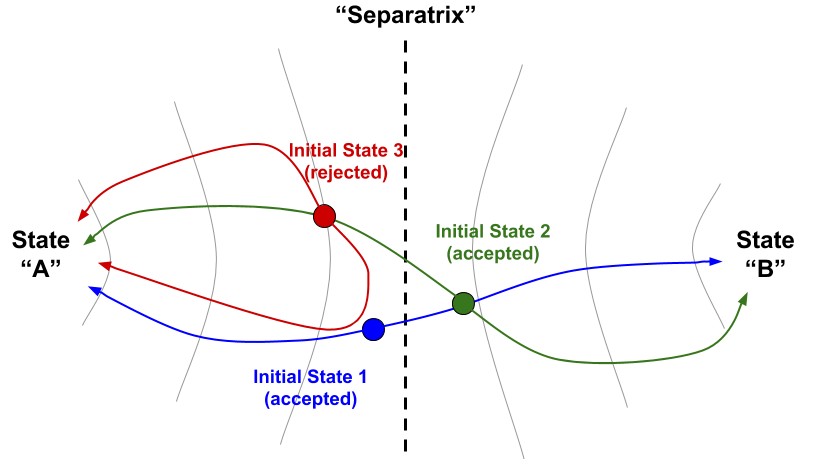

Aimless shooting is a method for sampling of the region of state space corresponding to the ensemble of transition states. Because by definition the transition state is a local maximum in energy along at least one dimension, this region is difficult to sample using conventional simulations – that is, a transition is a rare event. The aimless shooting approach is to leverage one or more putative or “guess” transition state structures, which will be “aimlessly” “shot” through phase space using unbiased initial velocities chosen from the appropriate Boltzmann distribution. The resulting trajectory is at the same time also simulated in reverse (using initial velocities of opposite direction and equal magnitude), and if after simulations the two trajectories converge to different pre-defined energetic basins (e.g., one “products”, one “reactants”), then the trajectory connecting them is considered a success. New starting points are daisy-chained from older successful ones by taking an early frame from the reactive trajectory as the initial coordinates, and in this way it is ensured that sampling remains within the transition state ensemble [1].

Figure 1: An example of three aimless shooting moves in a hypothetical 2-D state space. Each shooting move consists of an initial coordinate (colored circle) from which two trajectories begin in opposite directions (colored lines). If the two trajectories go to opposite basins (“A” and “B”), then the move is accepted and new initial coordinates for the next step are chosen from an early part of the accepted trajectory (as move 2 (green) begins along the pathway from move 1 (blue)). If a move is not accepted (move 3 (red)), then the next step would begin from a different point and/or with different initial velocities from the previous accepted move (not shown).

What is ATESA?

ATESA is a Python program that implements aimless shooting and several related methods, with the intent of making them readily accessible to non-experts without requiring them to write (or read!) code. It automates the aimless shooting process with a system of independent “threads” representing one particular path in the search through phase space. A thread has a given set of initial coordinates, which it repeatedly “shoots” until it finds a successful reactive trajectory, at which point it picks a new shooting point on the reactive trajectory and continues. Because threads run entirely in parallel, aimless shooting with ATESA scales perfectly so long as sufficient computational resources are available.

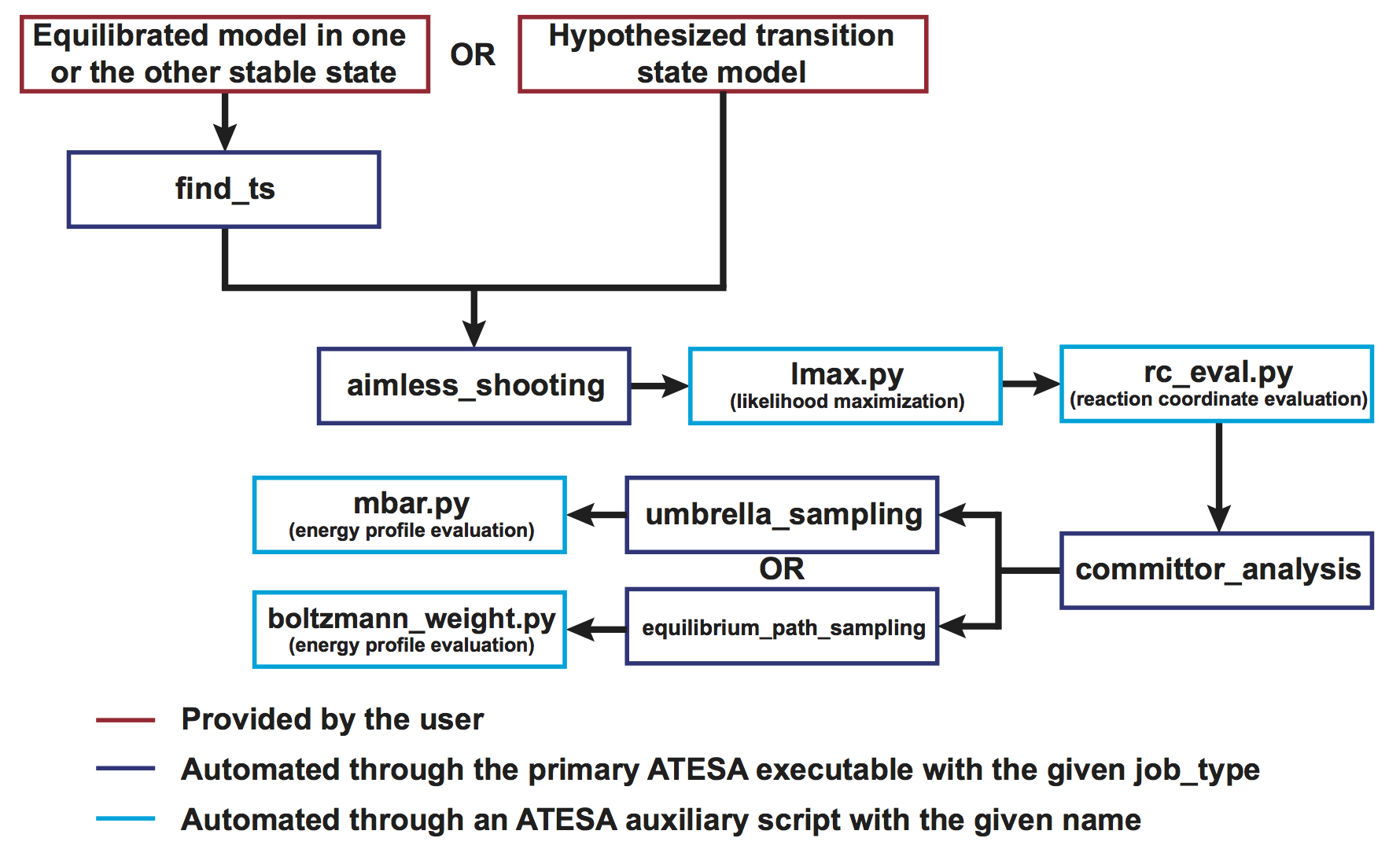

ATESA also features a suite of analysis and utility tools that run in much the same fashion. Most importantly, once aimless shooting has been completed, ATESA can be used to automate likelihood maximization to “mine” the data for a reaction coordinate that describes the transition path, committor analysis to verify that reaction coordinate, and equilibrium path or umbrella sampling to obtain the free energy profile along it.

Figure 2: The complete workflow automated with ATESA. Excluding the initial model, every step from start to finish is automated.

By design, ATESA is suitable for researchers who are familiar with the basic tenants of molecular simulation, but may not be experts in Python or in rare event sampling. By providing tools and guidance for a ready-made workflow from start to finish, ATESA aims to take the guesswork out of adding transition path sampling to your toolkit.

Example Reaction Study

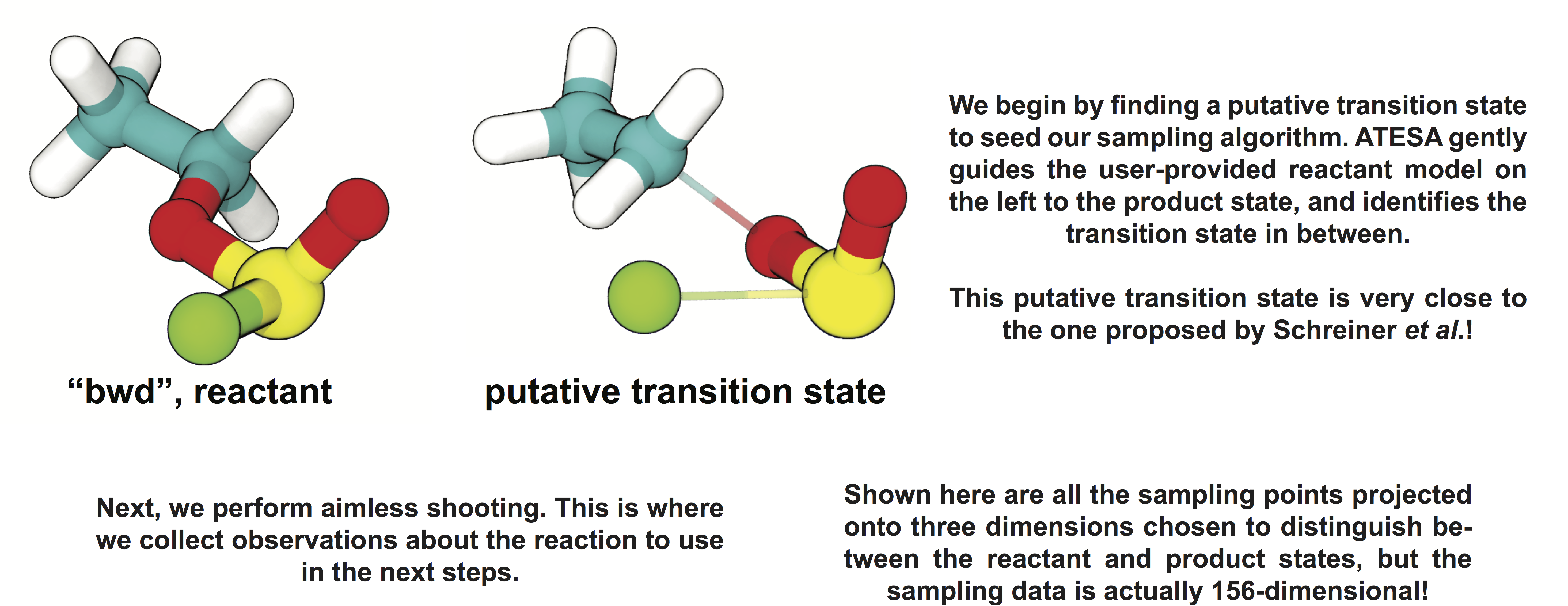

To demonstrate ATESA in action, we will look at a study for the gas-phase decomposition of ethyl chlorosulfite. We chose this reaction because the small number of atoms involved facilitate quick simulations and easy visualizations, but ATESA has also been successfully applied for much larger systems, such as enzyme reaction modeling.

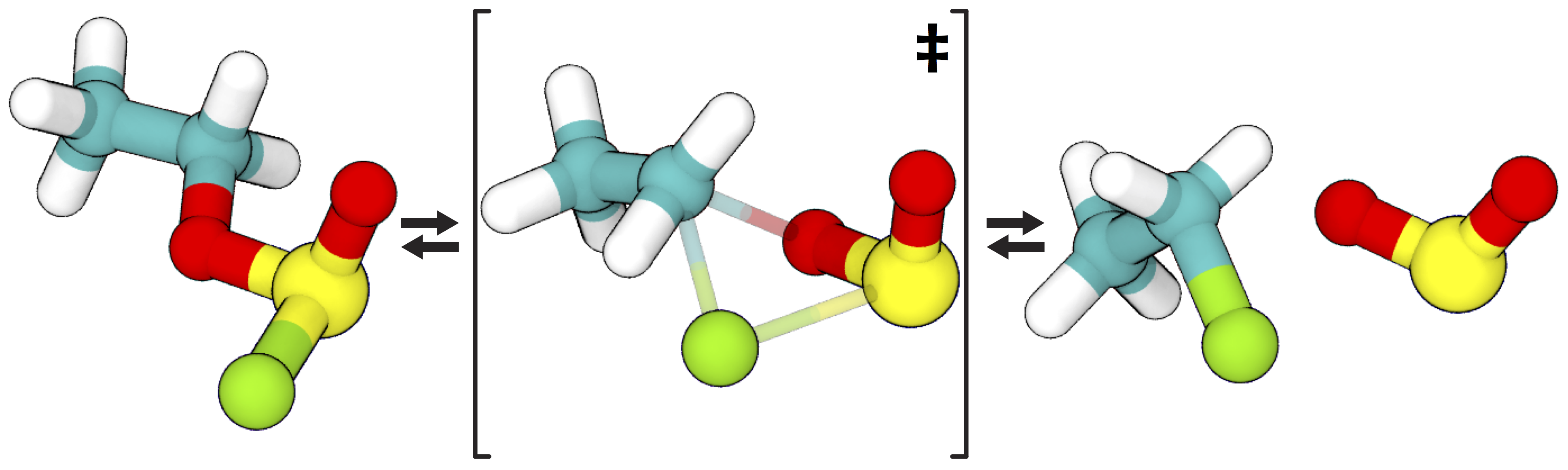

Despite its size, the ethyl chlorosulfite decomposition reaction is deceptively complex. Aurell et al. describe at four distinct possible mechanisms [2], and Schreiner et al. performed quantum mechanical calculations to identify the most favorable pathways under various conditions [3]. They argue that the most favorable pathway involves a “front-side attack” SNi mechanism as shown here:

Figure 3: The reaction pathway identified by Schreiner et al. [3] as the most favorable, recreated using VMD. Teal: carbon; white: hydrogen; red: oxygen; yellow: sulfur; green: chlorine.

We will not discuss the details of each step of the workflow here, but more information on this example study can be found on our documentation website, here.

Every step in this workflow (with the exception of comparison to results from existing literature, of course) has been performed automatically through ATESA, requiring no analysis or simulation effort on the part of the user. It is our hope that widespread use of this software will help make advanced sampling an accessible tool for chemistry and physics researchers not specialized in molecular simulations.

References

- Beckham, G. T.; Peters, B. In Computational Modeling in Lignocellulosic Biofuel Pro- duction; Nimlos, M. R., Crowley, M. F., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, D.C., 2010; Chapter 13, pp 299–332.

- Aurell, M. J., González-Cardenete, M. A., and Zaragozá R. J. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2018, 16, 1101-1112

- Schreiner, P. R.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Hill, R. K. Journal of Organic Chemistry 1994, 59, 1849–1854.

Acknowledgements

Tucker Burgin was supported by a fellowship from The Molecular Sciences Software Institute under NSF grant OAC-1547580