Reduced Density Matrix-Based Models for Strongly Correlated Electrons

Introduction

The development of accurate and efficient models for the description of electron correlation effects is an active area of research in quantum chemistry and molecular physics. Although popular models such as Kohn-Sham density functional theory (DFT) [1a, b] have been successfully applied to a wide variety of molecular systems, they often exhibit dramatic failures towards strongly correlated systems with dominant multireference character. In such cases, multiconfiguration pair-density functional theory (MC-PDFT) [2] offers a possible remedy towards a robust and economic deliniation of strong and weak correlation effects.

Since almost all methods built upon the merger of multireference approaches and DFT (MR+DFT), suffer from double counting of electron correlation, symmetry dilemma, and computational cost barrier of multireference methods, this poster intends to show how reduced density matrix (RDM)-driven MC-PDFT model can simultaneously address all of these issues.

Theory

Throughout this section, we adopt the conventional notation employed within multireference methods for labeling molecular orbitals \(\lbrace \psi\rbrace\) : the indices \(i\), \(j\), \(k\), and \(l\) represent inactive orbitals; \(t\), \(u\), \(v\), and \(w\) indicate active orbitals; \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(d\) denote external orbitals; and \(p\), \(q\), \(r\), and \(s\) represent general orbitals.

Reduced density matrix-driven CASSCF method

The complete active-space self-consistent field (CASSCF) electronic energy can be expressed in terms of the active-space 1- and 2-electron RDMs [3]

\[E_{\text{CASSCF}} = (h^t_u + 2\nu^{ti}_{ui} - \nu^{tu}_{ii}) {}^1D^t_u + \frac{1}{2} \nu^{tv}_{uw} {}^2D^{tv}_{uw} \tag{1}\label{EQ:ECASSCF}\]defined as

\[{}^1D^p_q = {}^1D^{p_\sigma}_{q_\sigma} = \left< \Psi \left\vert \hat{a}^\dagger_{p_\sigma} \hat{a}_{q_\sigma} \right\vert \Psi \right> \tag{2}\label{EQ:1RDM}\]and

\[{}^2D^{pq}_{rs} = {}^2D^{p_\sigma q_\tau}_{r_\sigma s_\tau} = \left< \Psi \left\vert \hat{a}^\dagger_{p_\sigma} \hat{a}^\dagger_{q_\tau} \hat{a}_{s_\tau} \hat{a}_{r_\sigma} \right\vert \Psi \right> \tag{3}\label{EQ:2RDM},\]respectively. Here, summation over repeated labels is implied. In Eq. \eqref{EQ:ECASSCF}, \(h^p_q = \left< \psi_p \vert \hat{h} \vert \psi_q \right>\) represents the sum of the electron kinetic energy and electron-nucleus potential energy integrals, and \(\nu^{pq}_{rs} = \left< \psi_p \psi_q \vert \psi_r \psi_s \right>\) is an element of the electron repulsion integral (ERI) tensor.

The core idea of variational 2-electron reduced density matrix-driven (v2RDM)-CASSCF is that the spin blocks of the active-space RDMs can be determined directly by minimizing the energy with respect to variations in their elements and orbital parameters. Since all RDMs should be \(N\)-representable, the minimization procedure becomes a large-scale semidefinite program with polynomial scaling, the details of which can be found in Ref. 3.

Multiconfiguration pair-density functional theory

The MC-PDFT energy expression can be written as

\[\begin{align} E_{\text{MC-PDFT}} &= 2h^i_i + h^t_u {}^1D^t_u + E_\text{H} \nonumber \\\ &+ E_\text{xc} \left[ \rho,\Pi, \vert \nabla\rho \vert, \vert \nabla\Pi \vert \right] \tag{4}\label{EQ:EMCPDFT} , \end{align}\]in which, two-electron terms from Eq. \eqref{EQ:ECASSCF} (and the two-electron contributions to the core energy) have been replaced by classical Hartree term,

\[E_\text{H} = 2 \nu^{ij}_{ij} + 2\nu^{ti}_{ui} {}^1D^t_u + \frac{1}{2} \nu^{tv}_{uw} {}^1D^{t}_{u} {}^1D^{v}_{w} \tag{5}\label{EQ:EHARTREE} ,\]and the remaining exchange and correlation effects are folded into a functional of the on-top pair density (OTPD). As such, MC-PDFT addresses the double counting of the Coulomb correlation in MR+DFT framework. At the same time, symmetry dilemma has also been resolved via change of variables in exchange-correlation functional from spin densities to total density, \(\rho\), and OTPD, \(\Pi\).

OpenRDM Software Infrastructure

The OpenRDM package is an open-source software, hosting quantum chemical models such as MC-PDFT, which are designed for applications in large-scale calculations involving strongly correlated systems. In principle, OpenRDM can be interfaced with any program capable of providing 1- and 2-RDMs. For example, we have interfaced OpenRDM with Psi4 program package in order to adopt RDMs generated by v2RDM-CASSCF plugin. Its interface with CASSCF and DMRG modules in PySCF program package is under development.

Figure 1: OpenRDM package

Figure 1: OpenRDM package

OpenRDM’s source code resides in a version controlled public repository on Github. The code quality and security are continuously monitored via CodeFactor and LGTM services. For sustainability reasons, internal and external contributions through commits and pull requests are controlled within continuous integration and delivery pipelines managed by Travis CI service. Travis CI also automatically runs testing routines provided by CMake build system generator which handles fined-tuned relations among libraries and executables in our software. Documentation is generated by Doxygen and automatically deployed to the main branch via Travis CI.

Applications

In this section, we provide numerical evidence for the efficacy of our models in describing the electronic structure of strongly correlated systems. In particular, we apply (hybrid) MC-PDFT to compute singlet-triplet energy gaps of oligocene molecuels, dissociation potential energy curve (PEC) of \(N_2\) molecule, reaction energy barriers of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of ozone to olefins, and distribution of effectively unpaired electrons (EUEs) in zig-zag narrow graphene nanoribbons.

Singlet-triplet energy gaps of graphene nanoribbons

Singlet-triplet energy gaps of larger members of oligocene series not only shed some light on their fascinating opto-electronic properties but also reflect the key role electron correlation effects play in shaping their electronic structure.

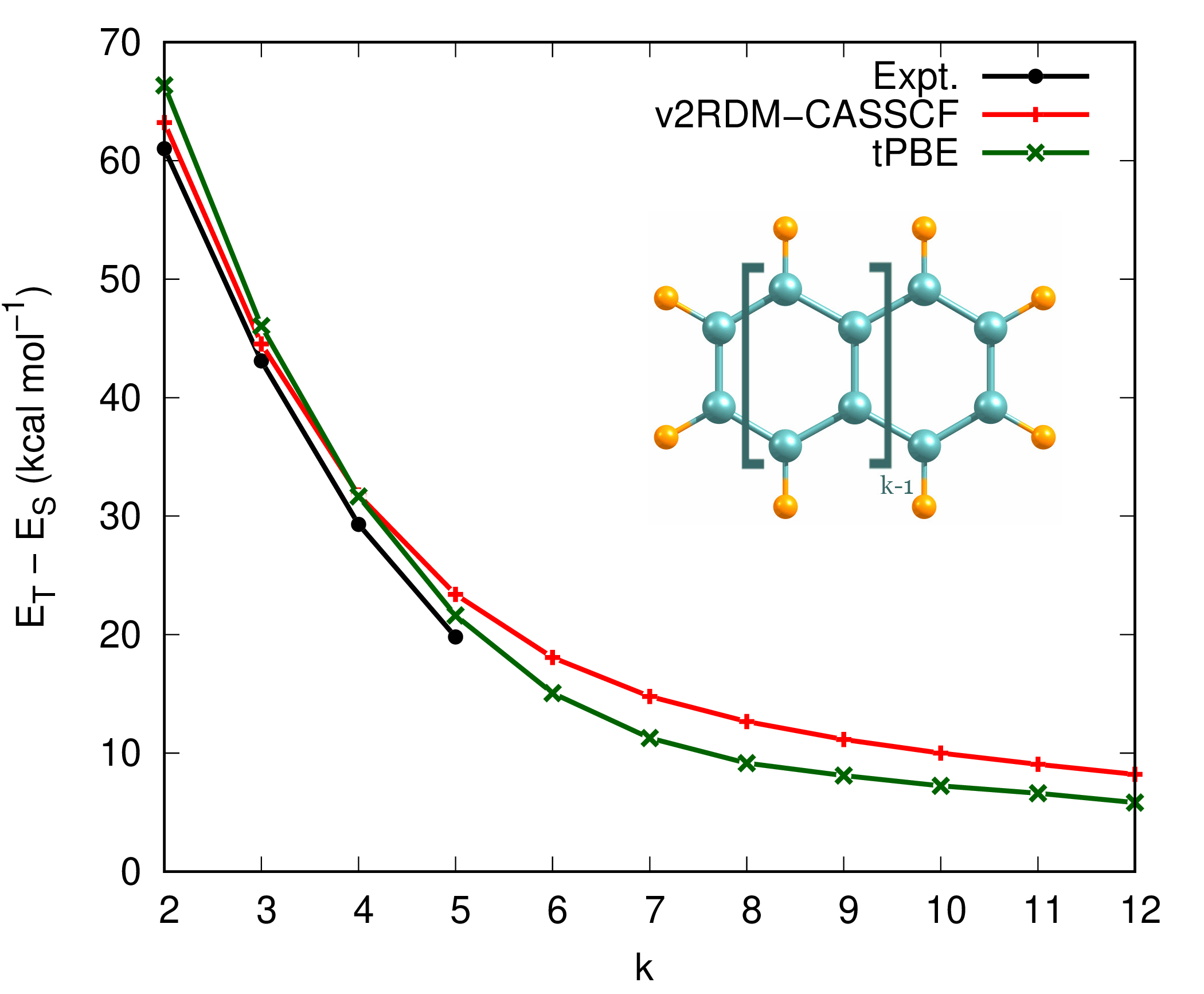

Figure 2 illustrates the singlet-triplet energy gaps of oligocene (\(k\)-acene) series where \(k\) is the number of fuzed benzene rings. All calculations adopt the full-valence active space of \(\pi/\pi^*\) orbitals and cc-pVTZ basis set. Translated PBE (tPBE) OTPD functional was used for MC-PDFT calcualtions.[4]

Figure 2: Singlet-triplet energy gaps of oligocene molecues

Figure 2: Singlet-triplet energy gaps of oligocene molecues

The v2RDM-CASSCF results in Fig. 2 display reasonable agreement with those of experiment for smaller members of oligocene series. However, a proper description of correlation effects, in particular, for larger polyacenes requires simultaneous account of static and dynamical electron correlation. Adopting tPBE density functional, one can capture dynamical correlation effects as well, which close the gaps as the number of benzene rings increase. The singlet-triplet energy gap value of 4.87 kcal mol\(^{-1}\), predicted by tPBE functional for infinitely large oligocenes, is in good agreement with the literature value of 5.06 kcal mol\(^{-1}\) from Ref. 5.

Molecular dissociation

The triple-bond dissociation of \(N_2\) molecule provides another example where accurate consideration of static and dynamical correlation effects becomes imperative.[4] The description of correlation effects within OTPDs can potentially be improved by counter-balancing delocalization error (DE) via replacing a fraction \(\lambda \in (0,1)\) of local exchange with its comlementary non-local part calculated from a multiconfiguration reference density. The resulting hybrid variant of MC-PDFT method is called \(\lambda\)-MC-PDFT.[6]

Figure 3 shows the non-parallelity errors (NPEs) of PECs, calculated with optimal \(\lambda\) values and various denisty functionals, relative to that of CASPT2. The NPE is defined as the difference in the maximum and the minimum deviations between the \(\lambda\)-MC-PDFT and CASPT2 PECs from an \(N-N\) distance of 0.7 Å to an \(N-N\) distance of 5.0 Å. The two- (and three-) particle constraints PQG(+ T2) are enforced on reference RDMs.

Figure 3: MC-PDFT and \(\lambda\)-MC-PDFT non-parallelity errors

(kcal mol\(^{-1}\)) associated with the dissociation of \(N_2\) molecule

Figure 3: MC-PDFT and \(\lambda\)-MC-PDFT non-parallelity errors

(kcal mol\(^{-1}\)) associated with the dissociation of \(N_2\) molecule

All NPEs presented in Fig. 3 exhibit their minimum values between \(\lambda\) = 0.70 and 0.90. Figure 3 also reveals that inclusion of nonlocal hybrid exchange effects indeed mitigates some DE so that the error associated with approximate \(N\)-representability of reference RDMs becomes dicernible. Furthermore, although NPEs can significantly vary over various choices of functionals, accounting for nonlocal exchange effects can serve as an efficient equalizer.

Reaction energies

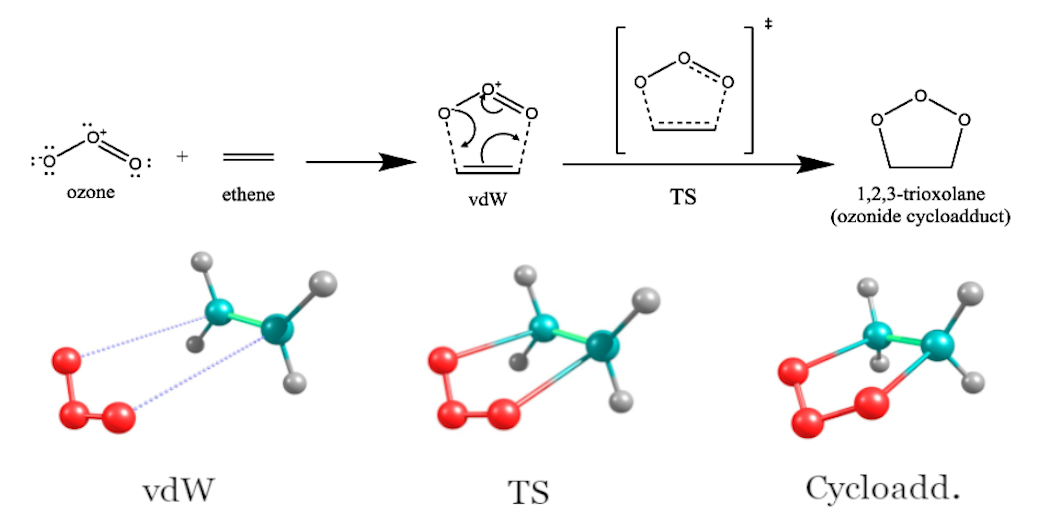

The O3ADD6 benchmark set is comprised of the energies of stationary point species with strong electron correlation associated with 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of ozone to ethylene and acetylene relative to the energies of isolated reactants (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of ozone to olefins

Figure 4: 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of ozone to olefins

Table 1 shows the relative energies of stationary points [the van der Waals complex (vdW), the transition state (TS), and the cycloadduct (cycloadd.)] and reactants in the O3ADD6 benchmark set calculated using hybrid MC-PDFT (\(\lambda\)-MC-PDFT) within aug-cc-pVTZ basis set. The active spaces of 2 electrons in 2 orbitals [denoted as (2e,2o)] and (4e,4o) were used for isolated reactants and stationary point molecules, respectively. Table 1 also includes the energies computed by the MC1H method of Ref. 7 as well as the best estimate values of Ref. 8.

Table 1: Calculated relative energies (kcal mol\(^{-1}\)) of stationary points and isolated reactants comprising O3ADD6 dataset

|

Method |

\(\lambda^a\) |

\[O_3 + C_2H_2 \rightarrow\] | \[O_3 + C_2H_4 \rightarrow\] |

MAE |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vdW | TS | cycloadd. | vdW | TS | cycloadd. | |||

| \(\lambda\)-tPBE | 0.20 | -0.40 | 7.69 | -68.00 | -1.86 | 4.87 | -57.57 | 1.29 |

| MC1H-PBE \(^b\) | 0.25 | -1.08 | 3.66 | -70.97 | -1.25 | 0.13 | -61.26 | 3.35 |

| MC1H-BLYP \(^b\) | 0.25 | -0.36 | 6.74 | -63.76 | -0.47 | 2.57 | -54.21 | 1.30 |

| Reference values \(^c\) | ——— | -1.90 | 7.74 | -63.80 | -1.94 | 3.37 | -57.15 | ——— |

| \(^a\) The optimal mixing parameter.\(~\) \(^b\) From Ref. 7.\(~\) \(^c\) Best estimates from Ref. 8. | ||||||||

According to Table 1, the mean absolute error (MAE) in the energies obtained via tPBE functional is 1.29 kcal mol\(^{-1}\) which is close to chemical accuracy and smaller than those computed by MC1H-PBE (3.35 kcal mol\(^{-1}\)) and MC1H-BLYP (1.30 kcal mol\(^{-1}\)).[7]

Effectively unpaired electrons

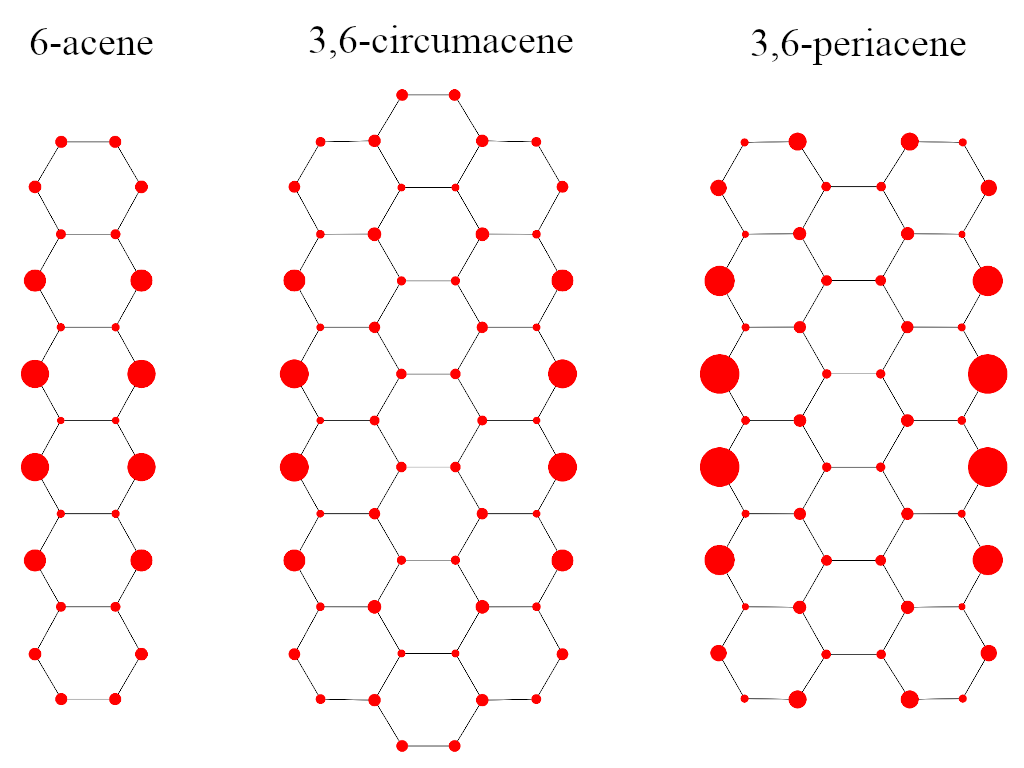

Effectively unpaired electrons (EUEs) offer a qualitative/quantitative tool for the analysis of RDMs. We adopted EUEs to investigate the di- and polyradical character of the singlet ground state of zig-zag narrow graphene nanoribbons.[9]

Figure 5: Spatial distribution of effectively unpaired electrons on graphene nanoribbons

Figure 5: Spatial distribution of effectively unpaired electrons on graphene nanoribbons

The spatial distribution of EUEs for 6-acene, 3,6-circumacene and 3,6-periacene molecules, demonstrated in Fig. 5, suggests that most EUEs accumulate on the zig-zag edges and towards the horizontal symmetry axis.

Table 2: Calculated number of effectively unpaired electrons for 6-acene, 3,6-circumacene and 3,6-periacene molecules

| Molecule | Total EUEs | EUEs on the edge |

|---|---|---|

| 6-acene | 2.47 | 1.24 |

| 3,6-circumacene | 4.41 | 1.17 |

| 3,6-periacene | 4.93 | 1.45 |

According to Table 2, the total number of EUEs in 3,6-periacene (4.93) is larger than those of 3,6-circumacene (4.41) and 6-acene (2.47), respectively. Nonetheless, the buildup of unpaired electrons localized on the edges shows a different trend. Again, 3,6-periacene shows the largest number of EUEs (1.45) on the zig-zag edge. However, the number of EUEs on the edge of 3,6-circumacene (1.17) is in fact less than that of 6-acene (1.24) which is somewhat surprising. Therefore, connecting open-shell character, stability and chemical reactivity in graphene nanoribbons based on the total number of EUEs should also be accompanied by their spatial distribution.

Conclusions

In this poster, we have overviewed the details of MC-PDFT and \(\lambda\)-MC-PDFT models designed for an accurate and economic description of the electronic structure of large-scale molecular systems with dominant multireference character. We have demonstrated that how RDM-driven MC-PDFT can address common problems in MR+DFT framework, namely, double counting of electron correlation, symmetry dilemma and computational cost barrier of multireference approaches. Adopting MC-PDFT, we offered numerical evidence for the efficacy of our models in describing the electronic structure of strongly correlated systems such as calculation of singlet-triplet energy gaps of oligocene molecuels, dissociation PEC of nitrogen molecule, reaction energy barriers of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of ozone to olefins and distribution of EUEs in zig-zag narrow graphene nanoribbons. All aforementioned models have been implemented in our open-source software, OpenRDM, which is freely available to the public.

References

- (a) P. Hohenberg and W. Kohn, Phys. Rev., 136, B864 (1964);

(b) W. Kohn and L. J. Sham, Phys. Rev., 140, A1133 (1965) - L. Gagliardi, D. G. Truhlar, G. Li Manni, R. K. Carlson, C. E. Hoyer, and J. L. Bao, J. Chem. Theor. Comput., 50, 66 (2017)

- J. Fosso-Tande, T. Nguyen, G. Gidofalvi, and A. E. DePrince, III, J. Chem. Theor. Comput., 12, 2260 (2017)

- M. Mostafanejad and A. E. DePrince III, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 15, 290 (2019)

- C. U. Ibeji and D. Ghosh, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 17, 9849 (2015)

- M. Mostafanejad, M. D. Liebenthal, and A. E. DePrince III, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 16, 2274 (2020)

- K. Sharkas, A. Savin, H. J. Aa. Jensen, and J. Toulouse, J. Chem. Phys., 137, 044104 (2012)

- Y. Zhao, O. Tishchenko, J. R. Gour, W. Li, J. J. Lutz, P. Piecuch, and D. G. Truhlar, J. Phys. Chem. A, 113, 5786 (2009)

- J. W. Mullinax, E. Maradzike, L. N. Koulias, M. Mostafanejad, E. Epifanovsky, G. Gidofalvi, and A. E. DePrince III, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 15, 6164 (2019)

Acknowledgements

Mohammad Mostafanejad was supported by a fellowship from The Molecular Sciences Software Institute under NSF grant OAC-1547580.