Gradients and Geometry Optimization with Multireference Wavefunctions

Introduction

In electronic structure, “active space methods” have been very successful for systems exhibiting strong electron correlation. However, their unfavorable combinatorial scaling has driven the search for new methods that better balance computational cost and accuracy facilitating their use with larger active spaces and larger systems. Modern methods, like density matrix renormalization group (DMRG), auxiliary field quantum Monte-Carlo (AFQMC), and full configuration interaction quantum Monte-Carlo (FCIQMC), have made important progress reducing the time and memory cost, but for certain systems the computational time is still prohibitive.

The goal of this project is develop a computationally efficient software to treat strong electron correlation that is easy to use and interface with popular quantum chemistry packages, giving users the ability to run geometry optimizations and nonadiabatic coupling calculations with active sizes that were previously impossible.

Heat Bath Configuration Interaction

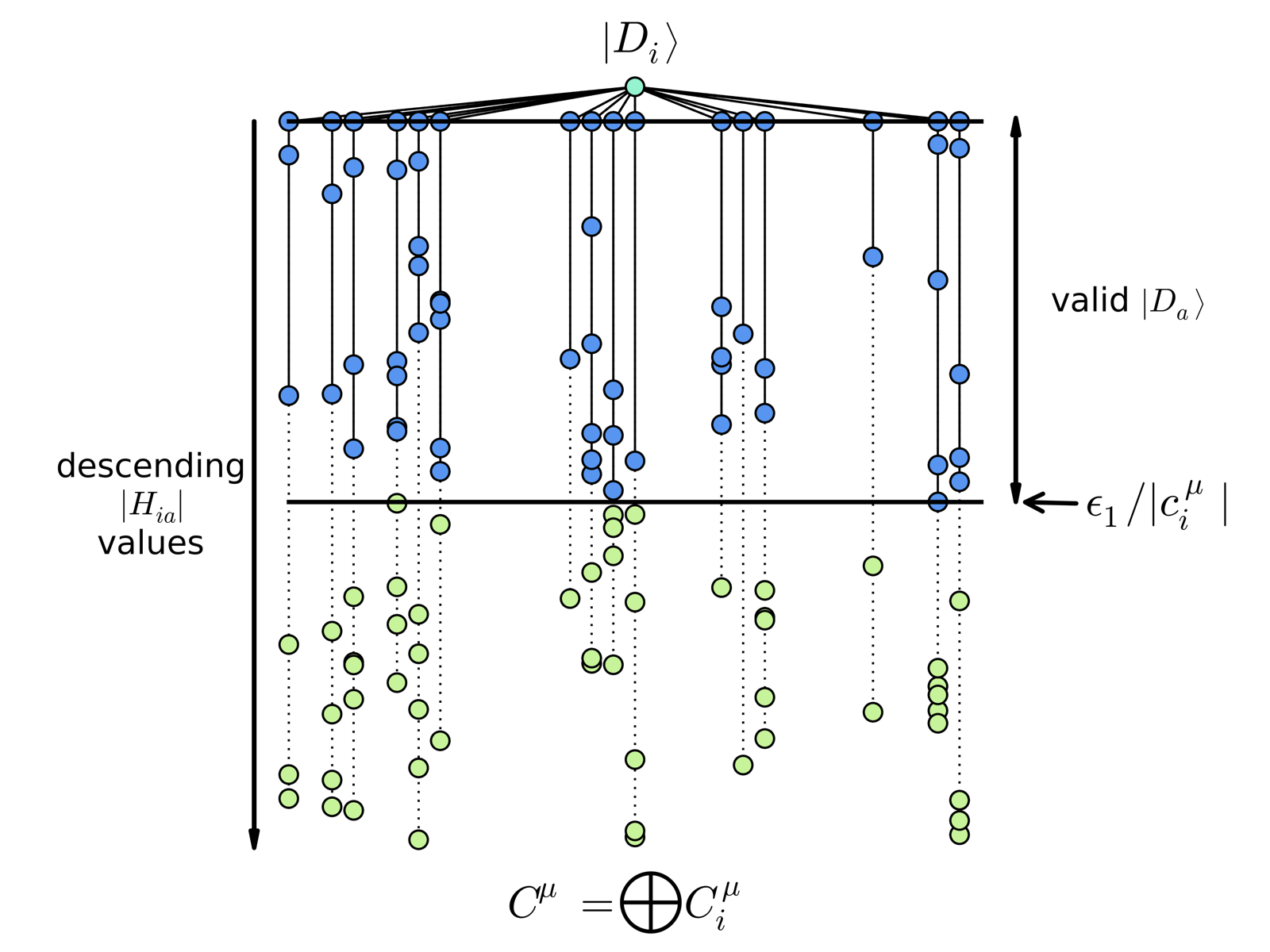

The general class of methods that perform a selected configuration interaction calculation followed by perturbation theory (SCI-PT) are an efficient alternative to traditional active space methods. Semi-stochastic heat-bath configuration interaction (SHCI) is a recently developed variant of SCI+PT. Like all configuration interaction methods, we express the wave function as a linear combination of determinants: \(\left| \Psi \right> = \sum_{i} c_i \left| D_i \right>\). In SHCI, the exact wave function is approximated by a more compact expansion, where only the most important determinants are kept. Following the variational optimization of this wave function, a perturbative energy correction from the remaining determinants is calculated semi-stochastically.

\[\max_{ D_i \in \mathcal{V}} \left|H_{ai} c_i\right| > \epsilon_1\]Equation 1: The criteria used to select the important configurations from the exact wave function to include in the SHCI wave function.

Figure 1: A visualization of the HCI selection criteria and how it can save considerable time by never visiting weakly connected configuration, shown in green.

Nuclear Gradients of SHCI Wavefunctions

Extensive testing of SHCI wave functions using finite difference confirms that even very approximate wave functions (those that are expanded using only a small subset of the possible determinants) have stable analytical gradients. Similarly, when using these gradients to perform geometry optimizations, we find that even approximate wave functions produce gradients close to their exact counterparts.

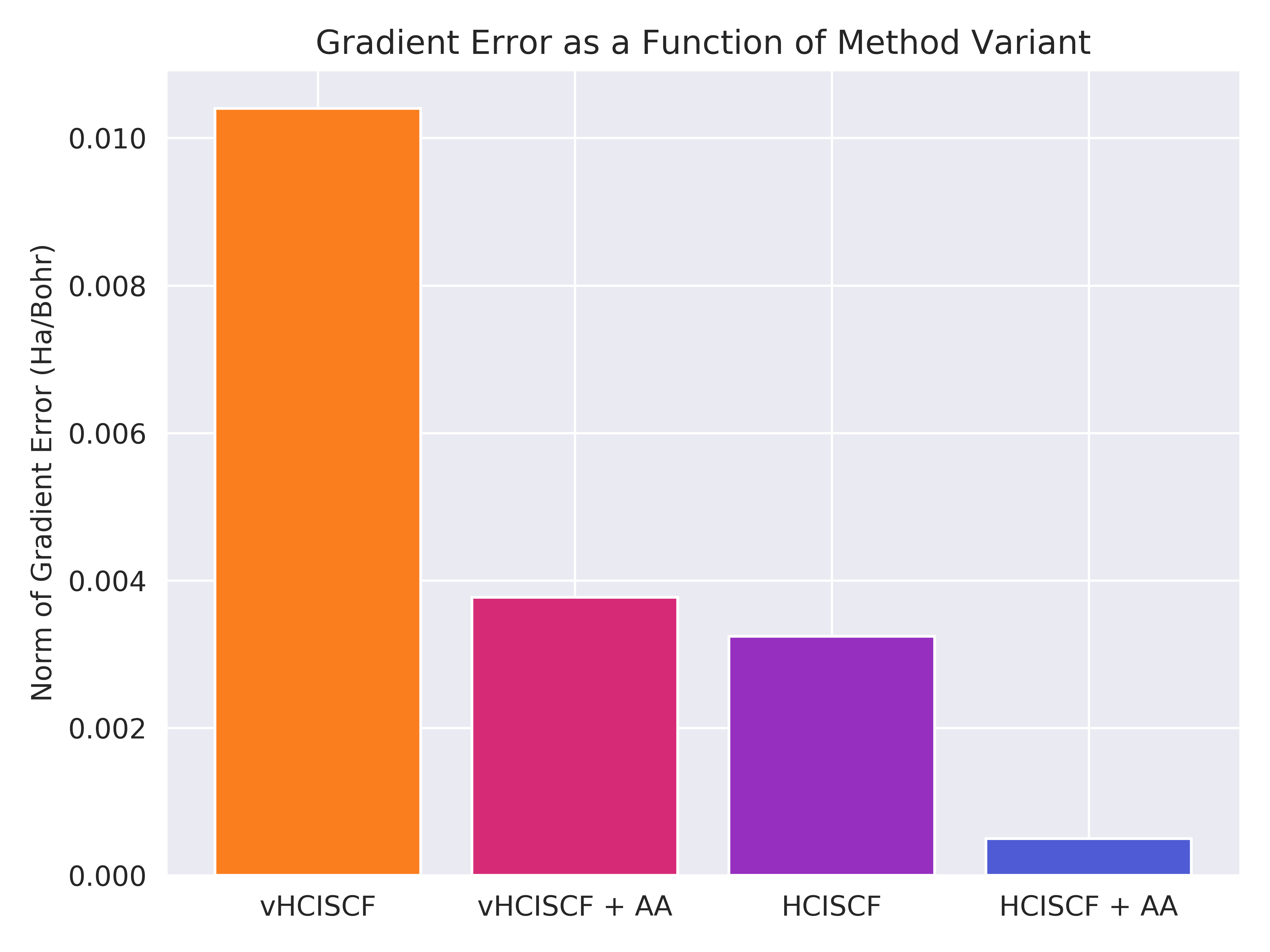

We find that gradients of very approximate variational wavefunctions (vHCISCF) can be improved in two ways (other than the \(\epsilon_1\) parameter): first, including a perturbative correction (HCISCF); second, by using optimizing active-active (AA) orbital rotations.

Figure 2: The gradient error as a function of method for the strongly correlated scandium dimer with HCISCF(6e,18o)/cc-pVDZ. [1]

Figure 2: The gradient error as a function of method for the strongly correlated scandium dimer with HCISCF(6e,18o)/cc-pVDZ. [1]

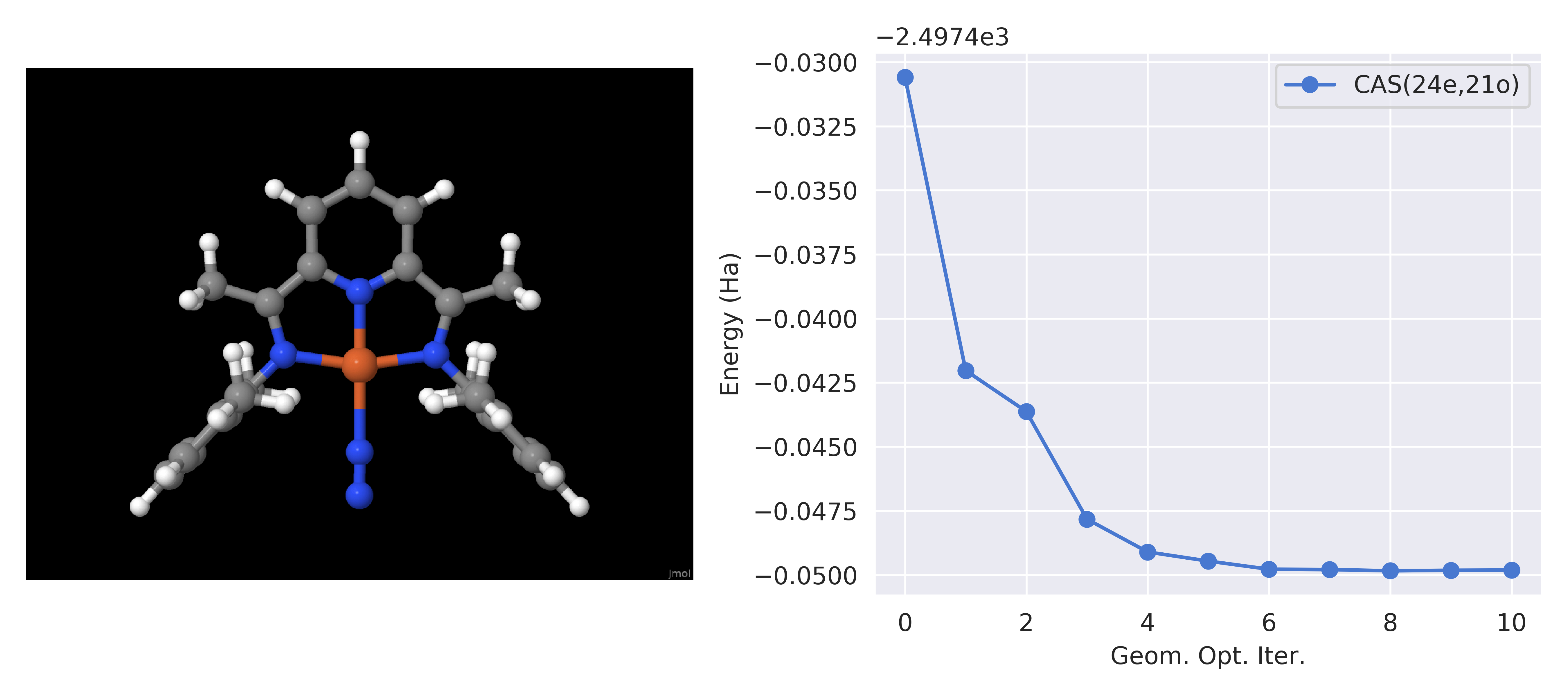

In addition to gradients, we have tested geometry optimization using HCISCF wavefunctions for model and realistic systems like the Fe(pyridine(diimine)) complex shown below. The pyridine(diimine) ligand is redox active in this species, leading to challenging electronic structure even for single point energy calculations.

Figure 3: The geometry optimization of the strongly correlated iron complex containing the noninnocent pyridine(diimine) ligand using HCISCF(24e,21o)/cc-pVDZ. [1]

Figure 3: The geometry optimization of the strongly correlated iron complex containing the noninnocent pyridine(diimine) ligand using HCISCF(24e,21o)/cc-pVDZ. [1]

Implementation

We want our method to help as many other researchers as possible and we know that a fast alternative to active space methods is needed in the electronic structure community. We also know that utility alone is not enough to make our software helpful to other researchers, it has to be easy to use as well. To achieve this, we minimize the number of steps for building, testing, and benchmarking the software. In order to accomplish these goals, our implementation of the SHCI algorithm, called Dice, is freely available and conatains:

- A mature build system using

Make - A thorough test suite

- Benchmarking suite with a variety of bash scripts to expediting testing the time and memory cost on new architectures

Impact and Future Work

Dice is interfaced with the open source quantum chemistry package PySCF [2,3], allowing users to calculate energies and optimized geometries with active spaces that are intractable using exact methods. Users can calculate approximate energies with over 200 active space orbitals and even optimize geometries for small molecules using approximate wave functions using nearly 100 orbitals.

We plan to implement the calculation of nonadiabatic couplings for multireference wave functions in PySCF. This will allow users to calculate couplings with exact or approximate wave functions and perform nonadiabatic dynamics calculations using previously intractable active spaces.

References

-

J. E. T. Smith, J. Lee, S. Sharma. “Gradients of Near-Exact Wavefunctions”. In preparation (2020)

-

Q. Sun, et al “Recent developments in the PySCF program package”. In Review (2020).

Funding and Acknowledgements

James E. T. Smith was supported by a fellowship from The Molecular Sciences Software Institute under NSF grant OAC-1547580

![]()