Optimal allocation for Free Energy Calculations

Introduction

Relative binding free energies

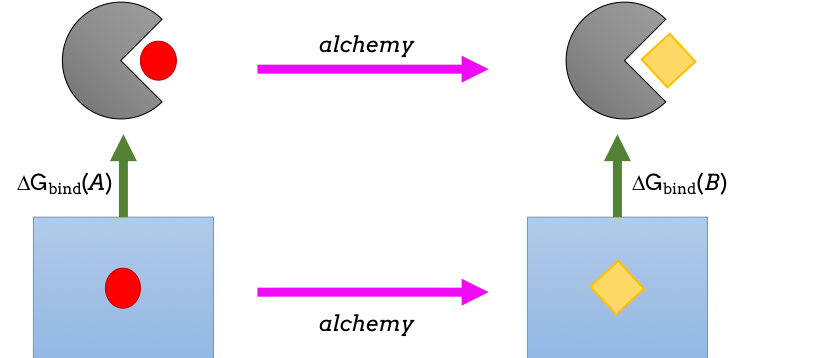

A relative free energy calculation involves perturbing one molecule into another, and calculating the free energy difference of making that change. Relative binding free energies (RBFE) involve the perturbing between two molecules, both in an active site, and in bulk water to calculate the difference in affinity between the two molecules. RBFEs are an effective tool in drug design, as they allow for predictions as to if making a change to a molecule will result in a more or less promising drug candidate (1).

Figure 1: Thermodynamic cycle whereby one molecule is ‘alchemically’ transformed into another. The difference between the two pink arrows affords the difference between the two green arrows: namely the difference in binding affinity of the two.

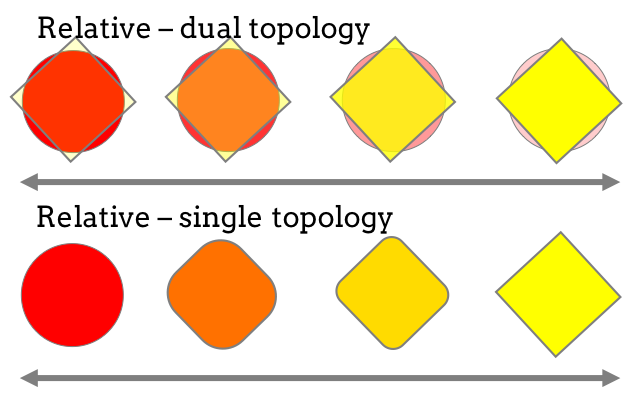

Perses is an open-source scientific software package for performing single-topology relative free energy calculations. Single-topology calculations involve simulating with a single hybrid ligand, that is perturbed across the lambda protocol to change from representing ligand A to ligand B, and differs from dual-topology type relative free energy methods whereby two ligands are present in the simulation, where the interactions of one ligand is turned on, while the other is turned off.

Figure 2: Different methods in perturbing between two ligands can be used: single-topology, which is implemented in Perses, and dual-topology.

Software

Perses is a python package, written to exploit the molecular dynamics (MD) functionality of OpenMM. The software is maintained on GitHub, and is developed using the MolSSI Software Best Practises framework. Python allows for the rapid development of novel and exploratory algorithms that are ‘developer-time’ fast, while performing simulations using the faster C and C++ software of openmm, which is ‘run-time’ fast.

Efficiency of RBFEs

Performing a RBFE calculation is computationally expensive. The expense of the calculation is mitigated if (a) the results are accurate - providing good experimental agreement and (b) the results are reliable - that they are precise. While simulations that are accurate can be achieved by longer simulation times and better physical modelling through improved atomistic forcefields, the precision of a calculation can be improved through choices in the alchemical design. For a given length of simulation (as the variance will reduce with increased simulation time), the precision, or hereforth the variance can be effected by the alchemical pathway in different ways -

- the nature of the alchemical species: for single topology methods, how the two ligands are combined to make a hybrid ligand.

- choice in alchemical protocol: the functions through which the interactions of the alchemical species are perturbed.

- the length of the alchemical protocol: wether that is the number of alchemical windows in a replica-exchange simulation or the switching time in a non-equilibrium switching simulation.

Optimizing these alchemical parameters will allow for more efficient simulation, such that results can be afforded with better certainty at a shorter timescale. Alternatively, which simulations are performed from a given set can reduce the variance of the results.

Experimental design

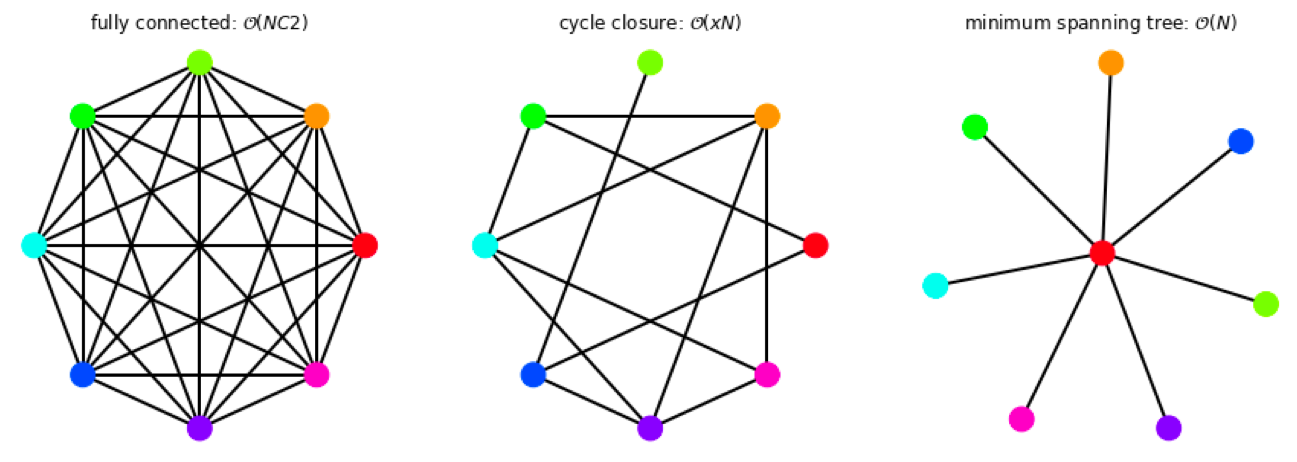

Relative calculations rely on choosing pairs of ligands to compare from a given set of molecules of interest. The minimum requirement to be able to fully rank set of molecules is that the pairwise comparisons between ligands results in a weakly connected graph - such that a pathway exists between any two molecules in the set. Even for a small number of ligands, there exists a redundancy in possible graphs that satisfy the connectivity requirement.

Figure 4: Selection of possible graphs for calculating relative free energies that satisfy the criteria of weak connectivity, where ligands are shown as colored circles and RBFEs are shown as the edges between them.

The number of RBFEs used (edges) will increase the computational expense, where the cycle-closure type graph is a compromise between the number of edges run, and having redundancy in the networks. Ideally, edges from all of the possible pairwise comparisons would be chosen in an optimal way, such as to minimize the variance.

Methods

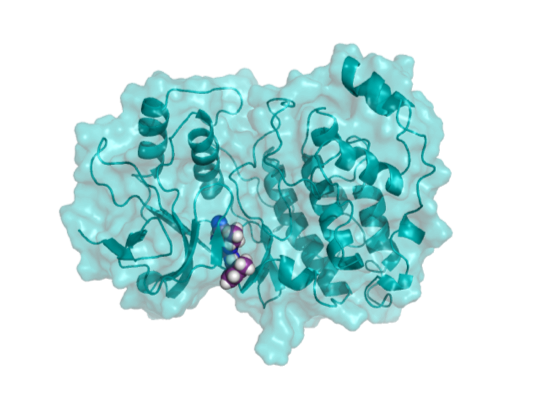

Relative free energy calculations have been performed using Perses, for a set of binders to the Jnk1 protein from the Schrodinger set (2). 100 forwards and backwards non-equilibrium (NEQ) switches of 1 ns, followed by 1 ns of equilibrium sampling at each endstate. While the small molecule forcefields differ, amber-14SB and TIP3P have been used. Input files are available. All simulations were performed on folding at home.

Figure 5: Jnk1 protein PDB: 2GMX

Results

Forcefields

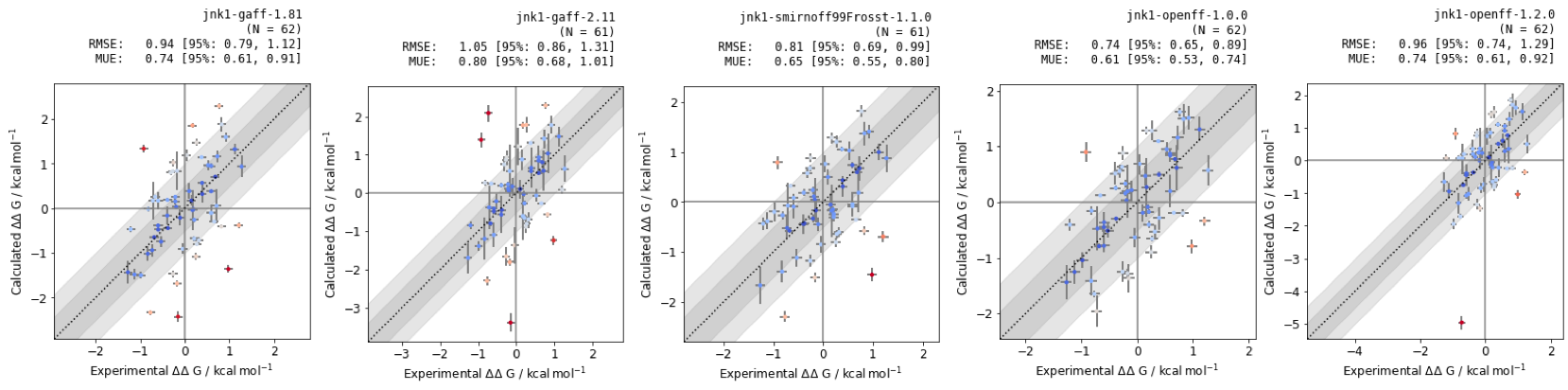

The RBFEs of the Jnk1 set have been performed for 5 different small molecule forcefields. Two versions of the generalized amber forcefield (GAFF) - 1.81 and 2.11, two versions of the open forcefield initiative - 1.0.0 and 1.2.0 and smirnoff99Frosst 1.1.0 were used.

Figure 6: RBFEs of Jnk1 dataset with different small molecule forcefields. RMSE and MUE are quoted in units of \(kcal mol^{-1}\), with confidence intervals calculated using bootstrapping.

The small molecule forcefield with the best statistical performance is openforcefield v. 1.0.0 for the Jnk1 target, however testing across different protein-ligand systems would be required for more thorough benchmarking.

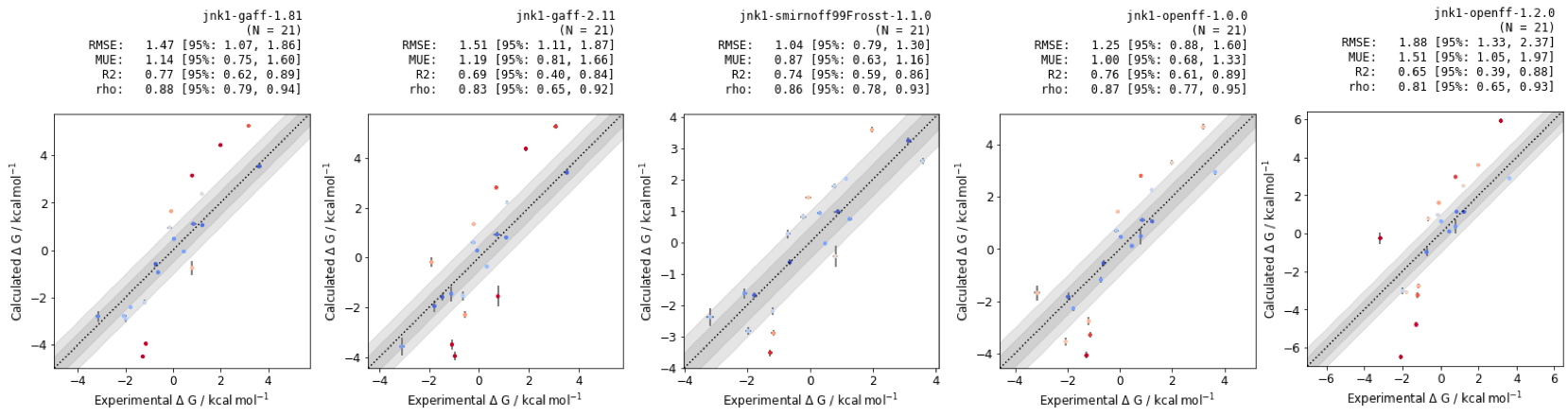

RBFEs provide pairwise comparisons between molecules, but for decision-making in live drug design projects, absolute free energies are a more useful metric. If there are resources available to make and test the best n predicted molecules, a maximum likelihood estimator can be used to optimize the graph of results.

Figure 7: Absolute binding free energies of Jnk1 dataset with different small molecule forcefields. RMSE, MUE, R2 and \(\rho\) are quoted in units of \(kcal mol^{-1}\), with confidence intervals calculated using bootstrapping.

While the RMSE and MUE of the methods differ in their performance, the small molecules perform similarly with regards to correlation statistics R2 and rho. These results suggest that relative free energy calculations would provide a useful tool for testing design ideas for future Jnk1 inhibitors.

Variance

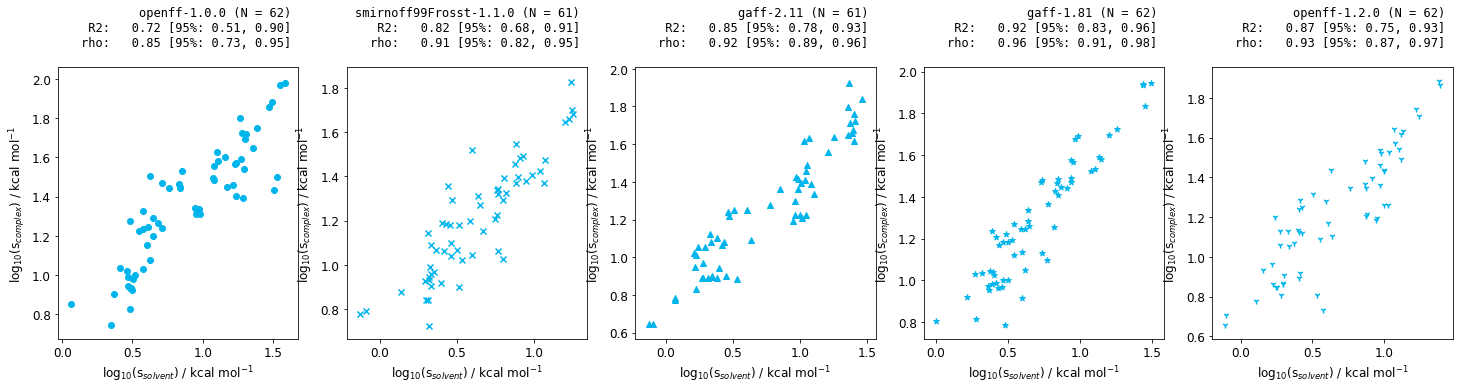

The above simulations were performed with the pairwise comparisons performed in Wang et al. (2), however the variance of those simulations aren’t all equal, and it is clear from Figures 6 and 7 that the errors associated with each RBFE are not equal. The statistical fluctuation of a relative free energy can be defined as:

\[s_{phase} = \sigma _{phase} * n_{samples}\]

Figure 8: Correlation between the statistical fluctuation of the solvent and complex phases for Jnk1 relative free energy calculations for a range of small molecule forcefields.

The above plots illustate there is a correlation between the statistical fluctuation in the solvent and the complex phases. As the solvent phase is much less computationally intensive, this would allow us to design better relative free energy networks for future iterations, resulting in faster simulations, with smaller associated errors.

References

- Cournia, Zoe, Bryce Allen, and Woody Sherman. “Relative binding free energy calculations in drug discovery: recent advances and practical considerations.” Journal of chemical information and modeling 57.12 (2017): 2911-2937.

- Wang, Lingle, et al. “Accurate and reliable prediction of relative ligand binding potency in prospective drug discovery by way of a modern free-energy calculation protocol and force field.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 137.7 (2015): 2695-2703.

Acknowledgements

“Hannah Bruce Macdonald was supported by a fellowship from The Molecular Sciences Software Institute under NSF grant OAC-1547580”